By Fernanda Paixão

Maricá, July 19, 2019

This question motivated me to meet the indigenous Guarani people of the Mata Verde village in Maricá-RJ. I had already read the indigenous anthropologist Sandra Benites and the philosopher Renato Nogueira writing about the Guarani’s peculiar care with babies. I was doing my master’s research on relational performance and I did some performances with babies at the Federal University of the State of Rio de Janeiro – UNIRIO.

I went to the village to do a performance with Guarani babies and listen to them. There were two days of meeting, the first one was of total strangeness, I brought objects, cloths that were part of my city universe and they wanted to know the spiritual meaning of each object, of my clothes, of my gestures. There was no spiritual meaning, it was movements, bodily experimentations. At that moment I was a stranger.

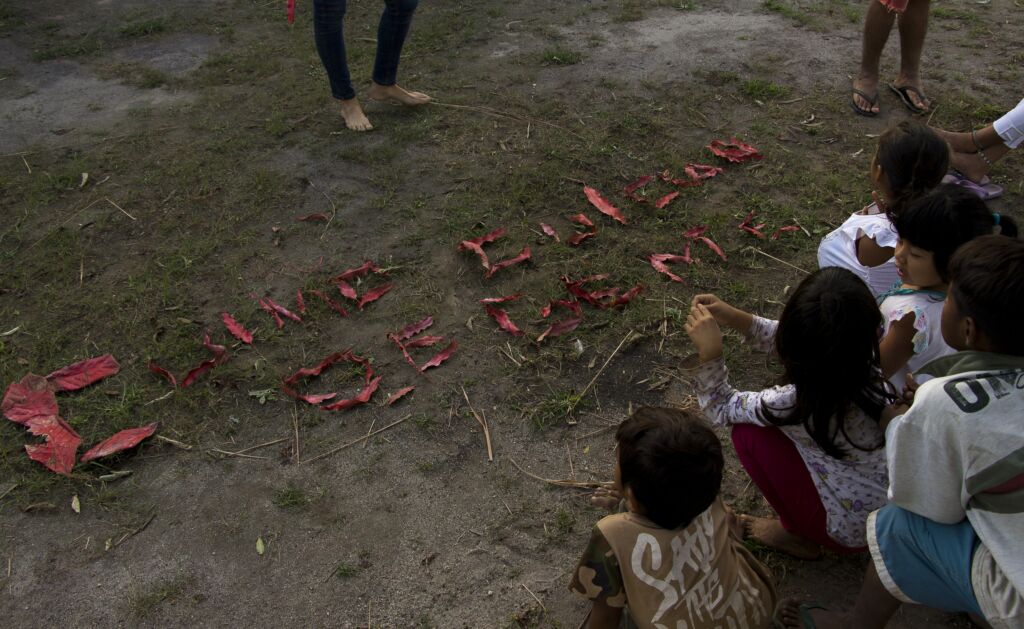

This strangeness, led us to a conversation about how to take care of people. They asked me to go back to the village, they were restless to know what was going on in the city school, because the municipality of Maricá had built a school inside the village, with the intention of serving the indigenous people. I went back to the village with dry leaves to write on that indigenous ground: How to take care of people? And to continue the conversation about school, education and care. I searched myself for the spiritual, soul meaning of the leaves and the question. I accessed an ancestral meaning of caring – the leaf that falls on the ground, protecting it from the sun. Life and death in the same being, the leaf being.

For the Nigerian sociologist Oyèronkè Oyewùmí, western culture has the body as the center of its thinking, mainly to banish it, to inferiorize it in favor of the mind, however the body, the visible, is still a western supremacy: “society is made up of bodies and as bodies – male bodies, female bodies, Jewish bodies, Aryan bodies, black bodies, white bodies, rich bodies, poor bodies. I use the word ‘body’ in two ways: first as a metonymy for biology, and second, to draw attention to the pure physicality that seems to be present in western culture.”

On the first day of the meeting, I had my white body and my movements as reference and difference. The objects I wore made sense in the city and continue to do so, but there they were the visible incomplete.

When I arrived on the second day, Cacique Amarildo received me and we sat down to wait for cacique Jurema. The cacique was busy and took a long time to arrive and then Amarildo told me: your job is to hold the leaves.

I was holding leaves for more than an hour in front of the cacique, some children, men and mothers. Meanwhile, they were drinking something from a plastic mug and asked me:

What happens to our children at school? What happens in the day care center? Why do they stay inside the classroom and not come outside? I could tell them what I have seen and experienced in schools as a teacher and a student. The shaman would like to meet with the teachers every morning to talk about the day’s activities. This was not happening. The performance became a space to listen to the anguish of the contact between city and village, between whites and indigenous people, between the western and the traditional peoples of America. A 500-year spiral that returned at the same point. How to be in contact with difference?

About Author

Fernanda Paixão is a multidisciplinary artist and researcher. She holds a Master’s degree in Performance Studies from Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de Janeiro – UNIRIO.